By Kay Humphries

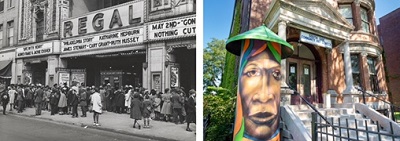

There is a lot of lore about Chicago’s fabled, African American community, Bronzeville Even its name conjures wildly disparate images for generations of Black Chicagoans. Some remember Bronzeville fondly, with bygone scenes of relatives all crowded together in small living spaces, yet feeling protected in the warmth of family. Others remember Bronzeville’s social life with people from “back home,” and acquaintances “just met,” all discovering a new world that wasn’t all that it was cracked up to be, but made better with friends. But, for the waning numbers of The Greatest Generation the second wave of “settlers” who survived The Great Migration, The Depression and World War II, Bronzeville meant familiarity in a strange and polarizing city.

Our grandparents and great grandparents evolved Bronzeville into a hybrid culture of southern roots adapted to northern realities. From foods, to music, to entertainment and even grooming, the result of trying to hold on to the core of their heritage and meld it with what was actually available to them, resulted in a community that relied on its members for cultural survival.

The Baby Boomers, being one, two or three generations removed from The Great Migration, and spread out into areas across the city, may not have had the firsthand experience of Bronzeville as a way of life, but they did have the influence and firsthand accounts of their family members… and luckily, they had a new Black consciousness emerging.

But, for the waning numbers of The Greatest Generation – the second wave of “settlers” who survived The Great Migration, The Depression and World War II, Bronzeville meant familiarity in a strange and polarizing city.

The Civil Rights and Black Power movements were major catalysts in awakening young Black people to the values of community and racial pride.

However, the promise of integration had already upended the village construct, as those who could, moved away from Bronzeville and other Black communities. Consequently, the Black neighborhoods lost the fundamental elements that made them viable. Not only did these neighborhoods lose their appeal, but they also lost their place as a sacred cultural influence in the mindset of younger generations. As Nathan Thompson, author of the highly acclaimed novel, KINGS, THE TRUE STORY OF CHICAGO’S POLICY KINGS AND NUMBERS RACKETEERS observes, “Look around you, today. Where is the legacy of Bronzeville? There is little evidence of the greatness that was.” Thompson also notes that this paradigm shift is not unique to Bronzeville. It’s happening all across the country, along the migration trail.

This is not meant to disparage the generations after the Boomers rather, it’s a statement meant to ignite the fires of respect and preservation from those generations who have the most to lose should this important piece of their history be erased. Organizations like the Bronzeville Community Development Partners, a 30 year private, non-profit founded by Managing Member at Bronzeville Partners L.L.C., Paula Robinson and the Black Metropolis National Heritage Area Commission, a 501c3 also founded by Robinson, are actively revitalizing the Bronzeville community as an international tourism destination. Through her leadership over two decades, the Commission’s advocacy has led to the completion of a formal feasibility study, as well as a legislative nomination to the Department of the interior for congressional designation.

These noble efforts are an attempt to keep a culture alive. As generations come and go, we lose more and more of our already sketchy past. And the preservation of who we are, and how far we’ve come becomes a personal responsibility.

The hope is that each one of us will teach the values of our past to the generations behind us. The hope is also that we will remember what it feels like to be a village with our families, our neighbors and our communities and that we can collectively feel the pride of being Black. It is the legacy of Bronzeville that we should never forget.