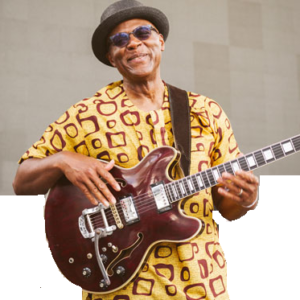

Musical Citizen of The world – by Donovan Mixon

As an undergraduate at Jersey City State College, guitarist Donovan Mixon was challenged by a professor to define his future goals in the form of a future newspaper article about his life fifteen years hence. His was entitled, The Quiet Career of Donovan Mixon. The article turned out to be prophetic because he has indeed accomplished everything described. For example, it stated that he had earned bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in music and had worked as a high school music teacher. However, it failed to mention that he had quit just before receiving tenure. Why? He says, “It would’ve been difficult to resign after getting tenure.” What followed was his Atlantic City period, performing as first chair guitarist for Resorts International and Atlantis Casino orchestras, backing vocalists such as Nancy Wilson, Dionne Warwick, and Englebert Humperdinck. He also backed the American comics of the day such as Jerry Lewis and Don Rickles. Being one of the four Black musicians working in the ten house orchestras at the time didn’t come without racial tension. “But,” Mixon says, “I had a secret weapon; my mentor and friend, Chris Columbo.” Legendary drummer, Chris Columbo and retired vice president of Local 661-708 A.F. of M. took young Donovan under his wing laying out the racist landscape of the day. A spry eighty-something, Chris had a long career leading groups for thirty-four years at Cliftons Club Harlem on Kentucky Avenue. His group backed all of the jazz greats of the day: Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Wild Bill Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Sammy Davis Jr. Dinah Washington and Louis Armstrong to name a few.

He spoke with a folksy cadence but with the wisdom of an urban hipster— “As a Black musician, beware of emotional traps set to get you labeled as a ‘difficult’ person (meaning negro) and ultimately fired.” Heeding his advice, Donovan survived tricky scenarios such as one that materialized during a certain Don Rickles Show. “I wasn’t a fan of Rickles. But the musicians were always visible on stage and were required to appear amused. Mr. Rickels aware of this, often went out of his way to genuinely crack up the band. This night, he was on fire. The band knew the punch lines so well we would at times mouth the words along with him. ‘I don’t know who you are in the middle, but you’re starting to get on my nerves.’ Still, no matter how many times I’d played the show, my spine would stiffen when he’d get around to his trademark racial humor: Black, white, red or yellow, it didn’t matter—he picked on everyone. And when he spoke of black folks, they were either singing, dancing, stealing or making trouble…all of the standard stereotypical bullshit of the times.

I needed the work, so I hung in, in spite of my inner conflict about his humor. Anyway, that night I eventually found myself falling in with the entire band, giving in to a near-fatal case of the giggles; until Rickels, leaning forward and winking at the audience, held his hand to the side of his mouth and whispered into the microphone… “Psst, are the spooks in the band laughing? They’re not reaching for their knives or anything, are they? One’s Puer- to Rican? Uh-oh, then the Puerto Rican and the colored guy are making plans to… ‘Roll the Jew’.” For a minute, I couldn’t feel sensation in my face and probably looked like someone who had been sucker-punched. I was pissed.” Be cool! I told myself and looked at Cliff, the other African American in the band who wouldn’t turn in my direction. The conductor started the next number which distracted me a little, but I was anything but cool. I thought of the wise words Chris may have said — stuff about keeping my cool ‘cause the dude couldn’t be talking about me. I thought, Who’s he talking about Chris? Th e f_ _ _ _ _ _ g SPOOKS in the band? What was I to make of this shit? Now, I’m a spook?’

I needed the work, so I hung in, in spite of my inner conflict about his humor. Anyway, that night I eventually found myself falling in with the entire band, giving in to a near-fatal case of the giggles; until Rickels, leaning forward and winking at the audience, held his hand to the side of his mouth and whispered into the microphone… “Psst, are the spooks in the band laughing? They’re not reaching for their knives or anything, are they? One’s Puer- to Rican? Uh-oh, then the Puerto Rican and the colored guy are making plans to… ‘Roll the Jew’.” For a minute, I couldn’t feel sensation in my face and probably looked like someone who had been sucker-punched. I was pissed.” Be cool! I told myself and looked at Cliff, the other African American in the band who wouldn’t turn in my direction. The conductor started the next number which distracted me a little, but I was anything but cool. I thought of the wise words Chris may have said — stuff about keeping my cool ‘cause the dude couldn’t be talking about me. I thought, Who’s he talking about Chris? Th e f_ _ _ _ _ _ g SPOOKS in the band? What was I to make of this shit? Now, I’m a spook?’

On the break Ron Ponzio, the musical contractor called for me to meet him in his office. As soon as I walked in he was like, ‘Look, Don, I know it’s rough out there. If you wanna go home, no problem.’ I could hear Chris’s voice in my head, ‘Don’t you f–ing go home!’ I thanked Ron and said that I wasn’t going any- where, but I wasn’t being paid enough to be called an f_ _ _ _ _ _ g spook. ‘Yeah, yeah, I know. I’ll tell him…’ he said, leaning forward in his chair. I turned for the door and said, ‘No Ron, I’ll tell him myself!’ Real fast, the dude ran from around the desk and blocked the door. ‘Look, Don. It’s cool. I get it; you don’t have to go home. I’ll tell him to lay off .’ The second half of the show went smoothly until the very end during the final bows. After shaking hands with the conductor and the con- tractor, Rickles on his way off stage stopped in front of me, looked me in eyes and extended his hand. I took it. He only said, ‘Sorry Don’ and walked off the stage.” In spite of the obstacles, Mixon worked as an orchestra musician for nearly five years while earning a Masters’s degree from Manhattan School of Music. As stated in his college article, future Donovan would eventually teach in institutions of higher education domestically and internationally.

Next stop: Berklee College of Music In 1986, he accepted a full-time offer to teach in the ear-training department. For Mixon, it was a twist of fate since ear-training was his worst subject in university. He turned this weakness on its head through a serious work ethic. He became one of the leading faculty members in the department recognized for experiments in Musical Aural Perception and a school-wide game-show called the ‘Big Ears Olympics’. This fruitful period was further distinguished in 1988 when he won an NEA grant for jazz composition. Then Berklee made a mistake. For two years in a row, they selected him to teach music clinics and perform in Perugia, Italy as part of the Umbria Jazz Festival. Donovan fell in love with Italy and soon took a one-year leave of absence from teaching for professional development. As per his contract, he resumed classes one year later only to resign after one semester to finish writing his ear training text and continue the new life he had begun in Italia.

He lived in Europe for eight years as a musical artist performing at the main jazz clubs: Café Bentivoglio and Chet Baker Club in Bologna, The Music Empire in Milan and festivals around the country: Monticello Jazz, Jazz In It, Fog- gia Jazz, Puglia Jazz. Mixon recorded two CDs as a leader for Philology Re- cords: 1993, Look Ma, No Hands! and in 1999, Language Of The Emotions. He also recorded a trio in 1995 with Lee Konitz, Free With Lee, Philology Re- cords – http://philologyjazz.wordpress. com/studio-catalogue/. Being a Berklee teacher earned him many invitations to music schools all over Italy to conduct workshops on the subject of performance ear training. These activities informed his research for his text Performance Ear Training, published by Advance Music of Germany. One year later, he accepted a full-time teaching position at Istanbul Bilgi University in the Republic of Turkey. At Bilgi, Donovan taught a full range of courses: Performance Ear Training, improvisation, ensembles, repertoire, and harmony. He was in good company with the late Butch Morris of ‘Conduction’ fame and virtuoso tenor saxophonist Ricky Ford. Donovan says, “Together with a talented Turkish faculty, we created a modern jazz scene that continues to this day.” The range of his travel for music clinics expanded from around Turkey to throughout the world: Bahcesehir University- Istanbul, Central European University – Budapest, Shanghai American School – China, School of the Arts Singapore. For ten years as a prime representative, Donovan has played in all of the major Turkish jazz festivals, spreading the word of Black music in a second foreign country. His third CD as a leader, Culmination, recorded in Istanbul, earned critical acclaim in Turkey and Chicago, eventually landing upon jazzchicago.net’s list of Top Chicago Recordings of 2010.

In 2010, he moved to Chicago and married his wife Diana who helps him raise his now 13-year-old son with whom he has reunited only three years ago after a tumultuous ordeal to get him back into his life. It’s Been Good, the song he composed for the mother of his son and just released in December 2019, is the centerpiece of a nine-month Give-Back crowdfunding campaign for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. While beautiful in itself, it shows the angst of a mother dying of cancer had to leave her toddler behind. Her pain was met with insult when postmortem, her family kept their child from Donovan for years. With the aid of a capable lawyer, Donovan mined his natural tenaciousness to get his son back. Now in coordination with NCMEC he has launched a Give- Back crowdfunding campaign for the organization. https://www.gofundme. com/f/it039s-been-good-giveback-campaign

This fifth chapter of his life (after Atlantic City, Boston, Milan, and Istanbul) includes working as a teaching artist and giving lecture workshops for organizations such as the Jazz Institute, JEN and Vandercook College. On top of this, in the works is an online Performance Ear Training course. Since arrival in Chicago, he has released a compilation of his European recordings and performs regularly with the Great Black Music Ensemble of the AACM. Donovan says, “It has been a humbling and eye-opening experience.” Since the 2017 publication of his novel, Ahgottahan- dleonit by Cinco Puntos Press, Donovan Mixon, guitarist, composer, recording artist, NEA recipient, college professor, academic, author, world traveler, novelist, multi-linguist and recent philanthropist has been described as one of those ambidextrous, crossover artists. We agree and look forward to what comes next.