...A Celebration of Illinois' New Poet Laureate, Seasoned With Some 5-7-5

First line: How are you doing?

When asked this by Parneshia Jones, her editor and Director of Northwestern University Press, Illinois Poet Laureate Angela Jackson complimented her assistants for typing and distributing work to the four poetry ambassadors she had selected.

Jackson’s response, the editor decided, needed revision. The answer, Jones clarified, should come from Angela Jackson the person, not the poet, not the artist.

“I’m doing better,” Jackson said, before allowing a pause to settle several silent seconds. “I’m so eagerly making a way out of no way that it’s hard to say. I just want to do what I have to do to survive.”

This admission led Jackson to reminisce about her mother, Angeline Robinson Jackson, whom she called “the center of my life.” She shared a memory about the Jackson Family matriarch, who died on Christmas, 2015.

“There would be days that were so bad that I would not want to get out of bed. But then I’d say, ‘You have to get up, because you have to fix Mama’s breakfast and get her situated,’” Jackson recalled. “We’d get our Cream of Wheat and apple sauce, (drink) our coffee, listen to the radio…and it would be better.

“I would go out and teach my classes at Kennedy-King College, and the students were a pleasure then,” she said. “When the students became not a pleasure – my last class, and it was also COVID – it was time to retire. And I did.”

Jones’ conversation with Jackson highlighted “Illinois Poet Laureate Angela Jackson: A Celebration,” presented by the Chicago Humanities Festival and held at the Reva and David Logan Center, on November 13, 2021. This event also featured Jackson’s prose, as read by other poets/admirers. Jackson, anointed the state’s fifth Poet Laureate in December 2020, has earned multiple awards — the Carl Sandburg Award, the American Book Award, and a Pushcart Prize, etc. – for her poetry, novels, and plays. A biography by Jackson, A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun, is about Gwendolyn Brooks, Illinois’ third Poet Laureate who was also her cherished friend.

When discussing Brooks, Jones noted, with admitted hesitancy, that her lights had been shut off when it was announced, in 1950, that she had won the Pulitzer Prize, becoming the first Black person to earn this honor. This led Jones to ask, “What does it mean to become (Poet Laureate)…at this moment?”

“It’s a lot of work to represent the people of Illinois and poetry at the same time,” Jackson responded. “It’s a lot of work to create ways to make people excited about poetry, (care more about) poetry, and get them to read poetry and create their own poetry that defines their lives.

“You have to work hard to create (these) avenues,” Jackson continued, before discussing funds she received from the Academy of American Poets to find the poetry ambassadors, who are all in their twenties. “I haven’t sent the ambassadors out yet, but if they have to…they will do virtual readings if they cannot do person-to-person.”

Jackson has already given numerous readings in her new position, virtually and in-person, including one at the Ethnic Heritage Museum in Rockford, and downstate.

Second Line: I want you to have flowers

Jones began at Northwestern University Press as a marketing assistant eighteen years ago. There, she became familiar with, and worked on, Jackson’s books. Jackson’s impact on her professionally and personally, she said, has been life affirming.

“I stand as a woman who has reached a point in my life where I want you to have flowers,” Jones said directly to her mentor. “And I want all young women who come after you…to get their flowers now.”

Jones then recalled and read Jackson’s “The Mother Behaves Like a Young Woman with a Lover when Nat King Cole Comes on the Box.” This creation, from Solo in the Boxcar Third Floor E, rescued her life and rejuvenated her mind during a tenuous time.

“It was so simple and…beautiful. It made all the difference in how we look at each other,” Jones said. “I wanted to do this poem, especially, because of all that we have gone through. It’s the simple things. We don’t necessarily have to go out.

“We have had to make do and survive inside, inside our shells,” Jones continued. “This poem actually speaks to everything that has happened before, everything that happens now, and everything that happens going forward.”

Here is a portion from said poem: “Nat King Cole’s glossed hair glistens like an onyx. His voice shines in her eyes. She closes them. His song ends on the edges of her Mona Lisa smile.”

This celebration culminated with Jackson sharing her art through voice, and, briefly, vocals. George Jr., her oldest brother, had asked her to read “Rock and Roll Monster: Down Home Blues Goes Hollywood.” This poem, from Dark Legs and Silk Kisses, The Beatitudes of Spiders, with the inscription “5527 and the television tribe,” chronicled a Jackson Family ritual held at their 55th and Wentworth Avenue home: watching movies together on a Saturday night.

“That was also the beginning of the Civil Rights movement, when the status quo was upset,” Jackson said. “So all of that was reflected in these movies, and this one is based upon The Spider. The whole plot is in this poem.”

And a portion of the poem paints like this: “She just wanna pick her teeth, snap her fingers, drink a bloody Mary, and listen to some down-home blues. Loud. She wanna lay around with her hair wild and legs un-styled. Smell her own funk and dream the rest of her cave-black night.”

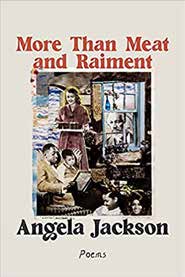

Jackson’s next poetry collection is More Than Meat and Raiment. “I am so excited about this book,” she said. “I cannot tell you how excited I am!”

“For Our People,” the collection’s closing poem, is a tribute to Margaret Walker’s “For My People,” first published in 1942. “I was lucky enough to see Margaret Walker read her poems in a classroom at Northwestern, when I was a student,” Jackson said. “She was my Afro-American Literature teacher.”

The title poem, which includes an acknowledgment to poets Cornelia Spelman and Reginald Gibbons, begins:

“Perhaps dream figures of fire and wind Spirit-being gathered up in human being momentarily More than flesh and flashy garments More than supper and skin of many colors More than meat and raiment.”

Cover-design creator Krista Franklin, along with celebration cohost avery r. young, Tiff Beatty, Dr. Tara Betts, and Haki Madhubuti, were among the poets who read Jackson’s words. (Madhubuti’s company, Third World Press, published Jackson’s first book, VooDoo/Love Magic, in 1974.)

“I thought of several words to describe Ms. Jackson: powerful, prolific, funny, and mischievous, if you catch her in the right moment,” said Betts, who shared “Cornerstone Woman,” an original poem she wrote to honor the Poet Laureate. It begins:

“Instead of talk about the one refused, we celebrate you, cornerstone woman A walking library, a syncopated thump shaking the terrarium of your ribs calling us to drums and blues like a slow drag on a checkerboard floor on a payday Friday night.”

Third line: We are the Jacksons!

“There’s nothing like being loved when you’re a child and knowing that you are loved. It carries over into your adulthood and saves you a lot of trouble.” – Angela Jackson, from the Logan Center stage.

Jackson acknowledged her parents, two brothers, six sisters, and Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) founder Hoyt Fuller on the dedication page in And All These Roads Be Luminous, published in 1998. Jackson’s firm family foundation, said Dr. Sheila Baldwin, associate professor at Columbia College, and her friend since the mid-1980s, is her strength.

“Everybody stays together without being show boatish or pompous,” said Baldwin, who met Jackson when they taught at Columbia College. “With them, it’s like: ‘We may not come from an abundance of wealth, but our wealth is the ability to just be together. This is who we are. We are the Jacksons.’” A few months after Jackson’s appointment, Baldwin invited the Poet Laureate to speak to her class.

The course, Baldwin explained, explored how writers examined trauma in an attempt to heal.

Jackson’s poetry and presentation impressed much, Baldwin added, as she then shared a few written evaluations from the students.

“Angela Jackson’s poems tell of pain and the culture of the Black community, but they also speak to her personal life,” one evaluation began. “I appreciated our discussion about art and uplifting…stories of Black joy. We spoke about how often the media only depict the trauma of Black communities, when there is so much more that the community could represent.”

Another student wrote: “I found it intriguing how writing has been a way for Jackson to heal from grief and pain.” Jackson’s prose and personality, Baldwin added, are characterized by an absolute calm.

“It is through her soul, and it’s beautiful to witness,” she said. “Angela can pinpoint certain topics and then expand on them from an obscure point of view that you may not otherwise notice.”

Before retiring from Kennedy-King College in 2020, Jackson visited a Creative Writing class taught by novelist Giano Cromley. Jackson’s willingness to address questions and read her work, he noted, made for a totally positive presentation.

“I wrote up this summary that I sent to my students afterwards,” said Cromley, “and I was like, ‘These are some really amazing insights about writing.’ She was also so encouraging to them.”

And when Jackson reads her poetry, he added, something…happens.

“I remember the first time I saw her reading in 2005. I had a moment where the hair on the back of my neck stood up,” Cromley recalled. “It was like, ‘This is someone who is possessed by this divine spirit.’ It was really cool.”

The Souls of Children-Folk

The Souls of Children-Folk

Three weeks after the Logan Center event, Poet Laureate Jackson is the special guest for a Poetry and Kwanzaa Celebration. Hosted by the Jack and Jill of America’s Chicago Chapter, and held virtually, approximately twenty children, ages five to seven, attend this event.

“How many of you like to go outside, stick your tongue out, and taste the snowflakes? Poems are like snow,” Jackson said. “If you write a poem, you can write one that is sad or glad, the way snowflakes are. Each poem is different.”

She then read “The Snow Poems” for the children.

“They melt on my tongue.

They are so much sweet

or so much grief,

a bliss beyond belief.

Now I’m making snow ice cream

Add milk. Add sugar.

The way I did as a child

When you eat it

you will cry”

“Why do people cry when they taste the snow ice cream?”

she asked, after finishing her read.

“It’s like they get a brain freeze, and it’s extremely cold,”

one child answered.

Poet Laureate Jackson then shared “Coda, the Spider’s

Mantra.”

“You could make a picture of your soul, of who you are

inside, like nobody else,” she said. And then she added

“Think of the sun

and memorize me,

a radiant web traps all light

and frees it

a luminous umbilical cord

frees all light

and frees it

Think of the sun

and memorize me…”

After this read, Jackson asked the children, “Who are you

like inside, when bringing yourself to other people?”

“I thought of the sun, and the first person I thought of was

Jesus,” said a child named Olivia. “Then I thought of myself,

and I thought about my personality.”

Jackson concluded by discussing Imani, Kwanzaa’s seventh

and final principle, which encourages faith.

“We have to believe in ourselves. We have to have faith in

our Black people and each one of us,” she said about Imani,

which is also her niece’s name. “We have to believe in

ourselves and our potential to make the world a better, more

beautiful place, by using our gifts of creativity.”