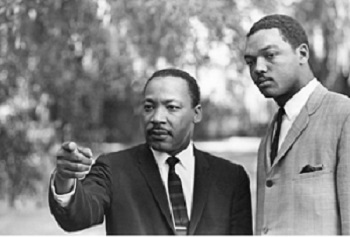

By the 1960’s it became apparent that racism and segregation were not confined to the South. Indeed, the City of Chicago was seen as severely segregated, causing Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr to write, “I have never seen, even in Mississippi and Alabama, mobs as hateful as I’ve seen here in Chicago.” It was this hatefulness and racism that caused Chicago community leaders and clergy to beckon Dr. King to Chicago.

Dr. King did not come to Chicago alone. He brought with him civil rights activists and organizers who had worked with and for him in the segregated south. Among those who came to Chicago with Dr. King in the 1960’s was twenty-five-year-old Jesse Louis Jackson.

Jackson had been active in the civil rights movement since he was a nineteen-year old college student, when he took a break from college to join seven other African Americans in a sit-in at the Greenville Public Library. In 1965 he participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches, which were organized by Dr. King, James Bevel and other civil rights leaders in Alabama. Those who saw Jackson in action were immediately impressed by his drive, and Dr. King was no exception. Dr. King began giving Jackson a role in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and when he returned from Selma, Dr. King charged him with establishing a frontline oce for the SCLC in Chicago. In 1966 Dr. King selected Jackson to head the Chicago branch of Operation Breadbasket, which was the economic arm of SCLC.

Thus, when Dr. King came to Chicago and began having weekly “cabinet” meetings in the oce of Edwin C. “Bill” Berry, Executive Director of the Chicago Urban League, what quickly came to Jackson’s attention was the de facto segregation that resided on Chicago’s south side.

Of course segregation was rampant throughout the city, but the south side (and west side) of Chicago had the largest Black populations, yet there were no Black cashiers in the supermarkets like Del Farms, High Low, A&P and others. Jackson began a boycott campaign, similar to campaigns initiated by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, that had been successful in other cities. Under the banner of Operation Breadbasket, Jackson’s campaign focused on white-owned grocery stores, soft drink manufacturers and dairy companies that made large profits in Africa American neighborhoods. He also advocated support of Black-owned banks as a route to economic development for Black communities. At those banks, Jackson argued, Black business owners were less likely to face discrimination when applying for loans.

Those of us living and trying to work on the south side of Chicago, particularly in grocery stores, saw the most visible success in the supermarkets. Back then, there was a butcher counter in the back of almost every supermarket, where butchers would weigh and cut the meat. Chickens, steaks, and lunch meats were not pre-packaged as they are today. You would seldom ever see a Black person as a butcher behind that counter in any supermarket. You would never see a Black cashier. Some supermarkets had perhaps one Black “stock boy.” Most had no Black employees anywhere in the store.

Jackson’s boycotts were effective. People began seeing a sprinkling of Black cashiers and a few Black butchers in most of the supermarkets, with a few exceptions. Del Farms, located on 63rd and Vernon Avenue, closed its doors rather than hire Blacks. Although EEOC (Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) had been in operation since 1965, Jesse Jackson’s boycotts caused the laws to work effectively against discrimination in the Black communities, as opposed to just being laws on paper only.

According to Stanford University’s King Institute: “Chicago Breadbasket went on to target Pepsi and Coca-Cola bottlers, and then supermarket chains, winning 2,000 new jobs worth $15 million a year in new income to the Black community in the first 15 months of its operation.”

George O’Hare, a former Sears Vice President and motivational speaker, spoke of meeting Jackson in his memoir “Confessions of a Recovering Racist.” O’Hare had begun working for Dr. King, and one day, he recalled, Dr. King said his work was taking him out of Chicago.

That’s when he introduced George O’Hare to Jesse Jackson. O’Hare subsequently met with Jackson in his Sears office and this is what he recalls about that meeting:

We began to talk about the problems of the world. As he (Jackson) went on with his world view, his perspective on what was going on in the political scene, and his predictions for the future, it occurred to me that I was sitting in the company of a twenty-five year old genius. For one so young to be so passionate about uplifting the Black race and helping to level the playing field was impressive to say the least. If I hadn’t been sitting there facing him I wouldn’t have believed that all of this wisdom could come out of the mind and the mouth of a young man only a few years out of his teens. We talked for over two and a half hours. I could see what Dr. King saw in this great young man.”

Jackson had brought with him to Chicago his young wife, Jacqueline, and his two children, three-year old Santita, and one year old, Jesse, Jr. Who wouldn’t have loved to be a fly on the wall in the Jackson household to hear what wisdom he imparted on his young children to cause them to grow up to be so extremely politically astute? Jesse Jr. was a United States Congressman, Santita is a prominent radio host and well-known vocalist, and their younger brother Jonathan was just elected to the United States Congress. The Jackson’s have two other offspring, successful in their own right: Yusef Jackson, and Jacqueline Jackson (who everyone calls “Little Jackie.”) Jesse Jackson founded Operation PUSH (People United to Serve Humanity) in 1971.

In 1972, he brought Black Expo to the Chicago International Amphitheater. The New York Times announced the impending Black Expo in a September 27, 1972 article:

1 Center to left:, Jackson’s wife Jacqueline, daughter, Santita, sons Jonathan,

Yusef, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Jesse Jackson Jr., and Jackie Jackson, Jr

“This year’s Black Expo, which opened here today . . . is the first annual black business and cultural trade exposition under the auspices of Operation PUSH.

While the S.C.L.C., founded in 1957 by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., languishes in Atlanta near financial death, the future never looked brighter for Black Expo and Operation PUSH — People United to Save Humanity.

Almost a million people are expected to visit Expo at the International Amphitheater on the city’s South Side, and gross receipts should be around $500,000.

The Rev. Jesse L. Jackson, the founder and head of PUSH, outlined an aggressive program for the organization, which is less than a year old.”

Reverend Jackson merged Operation PUSH with the Rainbow Coalition, which was founded in 1969 by Fred Hampton (now deceased). The Rainbow/PUSH Coalition staged several boycotts against major businesses based on their lack of investment in the African American community. As a result of the boycott of the Coca Cola beverage company and other major businesses, Coca Cola donated over $34 million to Black businesses. The Black advertising agencies, PR firms, and professional services companies grew and flourished, jobs for Blacks in the soft drink, beer and banking industries multiplied, nationally Black hi res, promotions and contracts grew. Reverend Jackson was in demand to negotiate Fortune 500 companies Moral Covenants to hire Blacks and purchase from Black businesses.

Rev. Jackson also established the PUSH International Trade Bureau, which continued in an advocacy position for decades to pair companies with qualified businesses.

The Black advertising agencies, PR firms, and professional services companies grew and flourished, jobs for

Bill Hampton (brother of slain leader, Fred Hampton) Jackson, Bobby Rush, & AAPL President, Renault Robinson

Blacks in the soft drink, beer and banking industries multiplied, nationally Black hires, promotions and contracts grew. Reverend Jackson was in demand to negotiate Fortune 500 companies Moral Covenants to hire Blacks and purchase from Black businesses.

Rev. Jackson also established the PUSH International Trade Bureau, which continued in an advocacy position for decades to pair companies with qualified businesses. In Chicago, the International Trade Bureau worked with Jewel Foods to train and develop more than thirty Black vendors who met weekly as PUSH opened doors in over 300 stores. Cub Foods and others set the model for grocers today in Chicago and across the country to follow the example. Surely billions in the hands of Blacks was the result of fifty years of economic focus.

In 1982, Reverend Jackson established phone banks at Operation PUSH to register new Black voters in order to help elect Chicago’s first Black mayor. With the help of the phone banks and the “Come Alive October 5” voter registration campaign, thousands of new registrants were directed to Operation PUSH to be signed up in time for the election.

After the second largest city in the United States acquired its first Black mayor, it made all the sense in the world to many people that the country was ready for its first Black president. It was no surprise at the time that the man who had done so much for the Black community, who had opened so many doors, who had leveled the playing field wherever he could, would run

for President of the United States.

Jesse Jackson ran for President in 1984, earning 3,282,431 primary votes, or 18.2 percent of the total that year. He won five primaries and caucuses: Louisiana, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Virginia, and one of two separate contests in Mississippi. There is no doubt in many minds that had it not been for racism, he would certainly have won that race.

In his 1988 presidential run, his successes doubled: Jackson captured 6.9 million votes and won 11 contests: seven primaries (Alabama, the District of Columbia, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico and Virginia) and four caucuses (Delaware, Michigan, South Carolina and Vermont).

It was around the time of his 1988 Presidential run, that Rev. Jackson led the charge to have our race referred to as African Americans as opposed to Blacks stating, “To be called African-Americans has cultural integrity. It puts us in our proper historical context. Every ethnic group in this country has a reference to some land base, some historical cultural base. African- Americans have hit that level of cultural maturity.″

Jackson not only sought to free American Blacks from segregation, racism, discrimination and oppression; he also sought to free all Americans from hostage situations, which speaks loudly to his patriotism.

In 1983, he traveled to Syria to secure the release of Navy Lieutenant Robert Goodman, who was being held by the Syrian government. After Jesse’s personal appeal to the Syrian government, Goodman was released.

In 1991, he went to Iraq to plead with Saddam Hussein for the release of foreign nationals being held as human shields.

Once again, he was successful, securing the release of 20 Americans and several British individuals. In 1999 he traveled to Belgrade to negotiate the release of three United States POWs (Prisoners of War). He met with Yugoslav president, Slobedhan Milosevic who agreed to release the three men.

If we count up the lives that Reverend Jesse Louis Jackson has saved, not just through hostage negotiations, but also by going to schools in Black communities and having children say “I am somebody!” If we count up the people who were inspired to do something with their lives to make a difference, because Jesse Jackson ran for President of the United States. If we could count the people who have better incomes because of the jobs secured by Jackson, better housing conditions because of the efforts of Operation PUSH, better education because of Jackson’s PUSH EXCEL Program. If you count up the people, Black and white, who have a different perspective of Black people because of the Black Inventor’s Booth at Black Expo – we could only conclude that Chicago is blessed to have this hero in our midst.