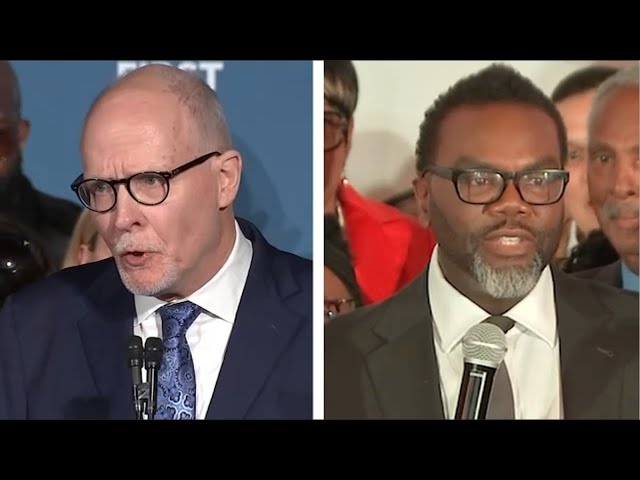

Mayoral runoff elections, like the one set for April 4, are a relatively new thing for Chicago. The vastly different circumstances and outcomes for the Mayoral runoff elections in 2015 and 2019 make it difficult to use historical precedent as an indicator for what might happen in the 2023 runoff election between Brandon Johnson and Paul Vallas.

Although Chicago municipal elections went non-partisan in 1999, we didn’t see out first citywide municipal runoff election until 2015 when incumbent Mayor Rahm Emmanuel beat Jesus “Chuy” Garcia. Until then Mayor Richard M. Daley 70+% general election victories were routine and more than sufficient to avoid the 50%+One threshold required to avoid a runoff.

Citywide offices for Treasurer and City Clerk were also usually decided on “1st ballot”, as were most aldermanic races. In 2003 only four Chicago Wards held runoffs for alderpersons. Therefore, Chicago doesn’t have much historical precedent for what usually happens with voter turnout in a highly contested runoff.

Given the stark differences between the Mayoral elections of 2015, 2019, and 2023, it is quite possible turnout for the April 4 runoff could easily go one of two ways- an unexpectedly large turnout in Wards where Vallas didn’t perform well (and slim victory for Johnson), or a citywide runoff turnout significantly lower than in the Feb. 28 general election (comfortable Vallas win).

It’s safe to say most everyone was surprised when in 2015 incumbent Mayor Rahm Emmanuel received only 45.63% of the general election vote against five candidates. The anemic general election turnout of just over 483K votes (34%) was easily surpassed by the 592.5K voters (41.04%) who showed up for the runoff.

While it’s hard to say just how large share of these new voters went to Rahm, he won the “undecided” votes (those who hadn’t voted for either of the Top-2 in the general election) by a 2-to-1 margin, easily beating Chuy 56-to-44%.

It seems one thing almost all the 2023 general election candidates were extremely successful at doing convincing voters Mayor Lori Lightfoot had to go. Any way you look at it, Lightfoot performed much worse as an incumbent Mayor in 2023 than she did as a 1st -time candidate in 2019. For starters, she received fewer total votes in 2023 (93K+) running against 8 opponents than in 2019 (97K+) running against 19 of them.

Newcomer Lightfoot’s stunning 2019 runoff victory over the veteran Preckwinkle, winning a citywide 73.7% of total votes cast and all 50 Wards, was an illusion of popular support, as barely a third of Chicago’s registered voters (527K) bothered to cast a vote. Chicagoans promptly set about ignoring Mayor Lightfoot’s attempts at dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic and other woes facing the city. Activists and operatives from all sides of the political spectrum immediately set to work casting her as a weak, inexperienced politician unable to deal with out-of-control violent street crime, deteriorating, dirty schools with ever lower educational standards, and militant public sector unions bent on squeezing city finances to fund their political activities. By the next election, voters had had enough. In the 14 out of 50 Chicago Wards where Lightfoot did win on Feb. 28th, the wins weren’t all that convincing in no Ward did she receive more than 42% of votes cast.

In many ways, incumbent Mayor Rahm Emanuel didn’t do much better in 2015.

While his margin of victory over Chuy Garcia was decisive, the 322, 171 votes he received amounted to only about 22.5% of registered voters. Not exactly a convincing mandate. I leave readers of this article free to decide how this affected Rahm’s ability to lead Chicago, but in the end, he did not attempt a repeat of Richie Daley’s long tenure as Mayor, deciding instead not to seek reelection for a third term. This is now the second consecutive Chicago municipal election that will produce a 1st term Mayor.

The only conclusive fact the topsy-turvy history of Chicago municipal elections has revealed: voter turnout in has rarely exceeded 40-42% of registered voters.

What it means, in effect, is that a small percentage of the Chicago’s registered voters, and an even smaller percentage of the city’s population, has an outsized influence over who determines fundamental aspects of how the city is run. This is likely to play the biggest factor in who becomes Chicago’s next Mayor, and with it the future of the city for decades to come.

I honestly don’t recall if in 2015 endorsements received by either Rahm or Chuy made a difference in the eventual outcome. It could be said Lightfoot’s resounding 2019 runoff victory made endorsements rather meaningless in that race. Again- the low voter turnout of Chicago municipal elections makes it difficult to analyze whether endorsements mean much beyond giving media outlets another story angle beyond opinion polls and candidate pronouncements.

If there are any aspects of the 2015 and 2019 Mayoral elections that could shed light on the outcome of this year’s race, it’s 1) what percentage of total votes cast went to the Top Two vote-getters, and 2) the difference in vote totals between the Top Two finishers. This is significant, in large part, because we can assume that anyone who voted for one of the Top Two in the general election probably didn’t switch their votes for the runoff. This means the election was decided by the relative handful of people who didn’t vote for the Top Two in Round 1, and the “new” voters who didn’t vote in the general election cast ballots for the runoffs.

Again we find no clear patterns that might help us determine what might happen on April 4.

In 2015, Rahm and Chuy received a combined 79% of total votes cast, 376.6K out of over 428K total votes. This left less than 100K voters from the general election who were “undecided”. Rahm’s 57K vote margin over Chuy established him the clear frontrunner but made eventual victory far from certain. At the time it wasn’t clear which way the “undecided” would vote, so it’s safe to say the additional 109K voters who turned out for the runoff election helped Rahm win.

In 2019, however, a packed field of 20 candidates meant the Top Two finishers Lightfoot and Preckwinkle received just 33.5% of total votes cast, with only about a 8,000 vote difference between them. Both candidates were effectively “starting from scratch”, because the voters carried from the general to runoff election didn’t make that much difference. The small amount of political speculation I’ll indulge in tells me widespread “anti-incumbent sentiment” prompted voters to choose Never-Been-Elected-to-Anything Lightfoot over Dean of Chicago politics Preckwinkle

This time around circumstances for the 2023 runoff are about midway between what we saw in 2015 and 2019. Collectively Brandon Johnson and Paul Vallas received about 54.5% votes cast in the general election, leaving a pool of “undecided” general voters slightly smaller than 2019’s Lightfoot vs. Preckwinkle contest, but significantly larger than 2015’s Rahm vs. Chuy election. However, unlike 2019 the vote difference between the Top Two is much larger, Paul Vallas besting Brandon Johnson by 60-65,000 votes. Vallas has a much longer record of public service than Johnson. In effect, Vallas is the “incumbent”, and like Rahm in 2015 has a much larger number of general election supporters going into the runoff.

The April 4 Mayoral runoff could help establish a clearer pattern of how Chicago voters behave, but it’s not likely. What is certain is that even a tremendously higher turnout than seen in the general election will still find a minority of Chicago’s registered voters who care enough to participate. The eventual winner will have not more than 22-to-24% of Chicago registered voters supporting him.

The consistent and overwhelming choice of Chicago’s electorate None of the above will likely have the greatest influence over the course of Chicago politics and the future of our city for decades to come.