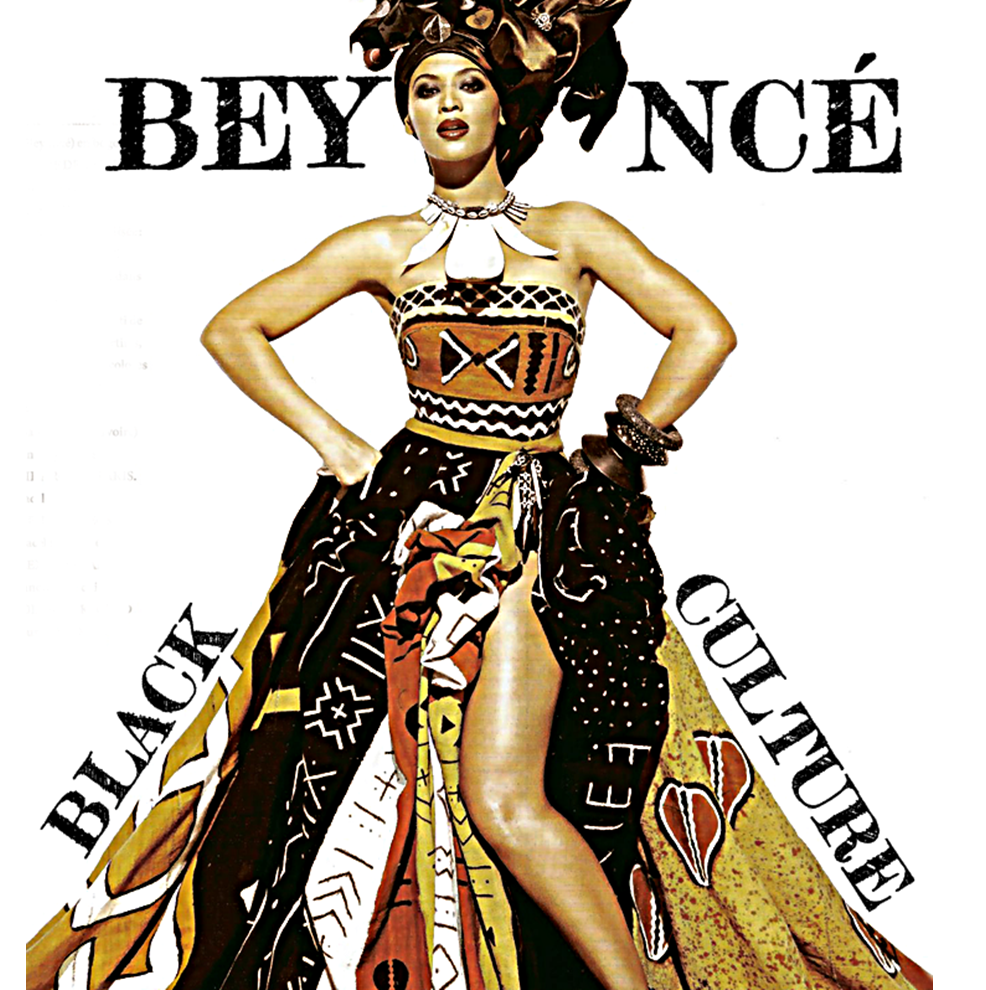

ueen Bey gifted us with a new Black anthem on the Blackest Juneteenth of my lifetime. It’s good news. The power of Beyoncé invoking the names of ancient African gods should not be undervalued.

ueen Bey gifted us with a new Black anthem on the Blackest Juneteenth of my lifetime. It’s good news. The power of Beyoncé invoking the names of ancient African gods should not be undervalued.

“Ankh charm on gold chains, with my Oshun energy.” “Baby sister reppin’ Yemaya”.

Those incantations for God are less familiar because of… generations of violence. Makes the song no less gospel. Modern-day negro spiritual. A political movement transformed into spiritual warfare. A possible consequence of the thread of conversations sparked in the unseen realm by George Floyd’s mama. Beyoncé has been heading in this direction. Something finally inspired her to say Her name -Oshun- and that matters.

Her husband has been on this path too:

“I got bloodlines in Benin, that explains the voodoo.” —Jay-Z (“We Family,” 4:44) “What ancestors did you summon to the summit To give me what I needed, what you need to take from ‘em.” —Jay-Z (“Adnis,” 4:44) “My saint’s Changó, light a candle El Gran Santo on the mantle” (“Pound Cake” -w/Drake) “I’m a page-turner, sage burner, Santeria Shango, December baby, my Orishas” —Jay-Z (“The Neverending Story” —w/Jay Electronica).

References to African spirituality from artists as successful as Jay-Z and Beyoncé offer unprecedented opportunity to reconnect African descendants across the diaspora to cultural principles that sustained us for centuries. They aren’t the first to reclaim the names of our Gods, but they are doing it from a platform louder than we have ever seen. It’s been commonplace to hear a slick line mention African spirituality at a local spoken word café like Larenz Tate’s character Darius Lovehall in Love Jones:

“Or maybe Queen of 2,000 moons Sister to the distant, yet risin’ star Is your name Yemonja Oh hell nah, it’s got to be Oshun”

Underground artists Digable Planets have made references to Orisha (the pantheon of gods in the Yoruba tradition, aspects of the One Supreme Being):

“It’s that certain style, uh huh Eshu-Elegba Squeeze off style quarters ‘til herbs get stressed Playin’ slick games and avoid all rest” Butterfly from Digable Planets, (“Slowe’s Comb”, Blowout Comb)

Jazz vocalist Lizz Wright made an incredibly important, easily overlooked, offering on her Fellowship album with a praise song to Oya in collaboration with Angelique Kidjo. Common also had a powerful line in Electric Circus, an album he was later oddly critical of:

“Offerings to Oshun, hoping war is over soon” —Common (“Aquarius”, Electric Circus)

All of these examples are relatively obscure. Able to be categorized as alternative, a polite way of saying weird. But Beyoncé. If her husband is a business, she is an institution. She is beyond mainstream. Beyoncé is in position to influence the minds of more Black people than all the psychologists combined. Sure there is sub-commentary about the cult of celebrity, but for now, let’s focus on what this could mean. When Beyoncé suggests we consider traditional African spirituality, it is significant.

Beyoncé is megachurch. I’m critical of prosperity preaching, but this time it’s valuable. For so long, messages about African values and culture have been dismissed due to the package by which they’re delivered. I can hold the attention of a group of young people for a moment, give them some food for thought. But my inspiration is short-lived, sometimes because they are actually hungry. So when I walk away in dingy shoes or drive away in my Chevy Cruze, I’m less appealing than my competition.

Rappers and presidents work hard, and pretend often, to display extravagant lifestyles so young people desire to emulate them. The same reason pastor pulls up in a Cadillac. Or jet. People don’t want to follow struggle. Faith leaders have particular pressure to demonstrate that their belief system will bring success. African cultural movements have stalled in part because we don’t look cool enough. We not accessible and appealing. Plus, we have not properly addressed the nagging question in the back of everyone’s mind: if African was so great then why did we lose?

Success is good. People want to be on the winning side. People want protection and independence. The issue is our definition of success, and it’s connection to European values and things. That’s not Beyoncé’s problem to solve. Beyoncé and Jay-Z aren’t visionary artists like Bob Marley, Nina Simone, or Fela Kuti, who directed shifts in culture. Beyoncé and Jay-Z are photographers. They are great at capturing the moment. That’s not a diss, we all play different roles. Every good artist isn’t good at reading the room #JCole. Beyoncé and Jay-Z are listening closely to the people. The congregation has a responsibility to tell the pastor that the helicopter is a misuse of funds, we would rather build another community center. We can tell Jay-Z what organization he should partner with instead of the NFL. We can tell Beyoncé her Black business directory is too cosmetic, she should connect with directories like The Black Mall who includes bookstores, schools, and everyday products like paper towels.

The power of the people must be exercised. We must demand real healing and institution building from our elected artistic officials, especially if they link their art to ancient African gods. Otherwise, artists will continue to do what they do best, perform.

Beyoncé is from Texas, the site of the Juneteenth origin story. She released “Black Parade” on Juneteenth to fortify the power of its spiritual invocation. Juneteenth 2020 was a particularly special moment. The abundance of Black pride. BLM protests. RBG everywhere. It was a much-needed boost.

“Black Parade” was the perfect soundtrack. Juneteenth 2020 was also a failure. Another missed opportunity to destroy the debilitating myth that freedom was ever granted by white people. The same narrative was repeated ad nauseum, enslaved Africans waited for 2 extra years for permission to be free. That explanation never felt right, because it wasn’t. Historian Hari Jones explains how Black people never sat idly by and waited for freedom, we fought for it. Lincoln did not “free the slaves,” we saved the Union and free’d ourselves. Seems like semantics, but the shift in language represents shifts in conceptualization, which creates shifts in power.

Less appealing aspects of the Black Lives Matter movement fit well with the false Juneteenth narrative, pleading to the morality of America. Asking to matter, to breathe, take the knees off our neck, is such a rudimentary request. The power structure remains intact, first in our minds, then in reality. That’s why it’s so easy for corporations to endorse BLM. Could you imagine the mayor of Washington D.C. renaming a street “Black Power” and painting it across the pavement?

What would’ve happened if we spent time during Juneteenth waving red, black and green flags, then sitting down with these fired up young people to study Marcus Garvey and the movement that gave us that flag? Instead of “Hands Up Don’t Shoot” they march through the streets echoing his words “Up you mighty race, accomplish what you will,” or “Africa for the Africans!”

That’s the kind of fire Beyoncé ignites when she invokes our ancestors and our Gods. She may or not be ready for that, but we can be. We must use this momentum, dig deeper into our culture, protect these flames from extinguishing, and keep this movement lit.

Adeyé Yohance, Ph.D. (Author of forthcoming book Discovering Black Spirituality: Practical Application of Ancient Wisdom)