Let America be America again.

Let America be the dream the dreamers dreamed

Let it be that great strong land of love

Where never kings connive nor tyrants’ scheme

That any man be crushed by one above.

(It never was America to me.)

O, let my land be a land where Liberty

Is crowned with no false patriotic wreath,

But opportunity is real, and life is free,

Equality is in the air we breathe.

(There’s never been equality for me,

Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”)

Who said the free? Not me?

Surely not me? The millions on relief today?

The millions shot down when we strike?

The millions who have nothing for our pay?

For all the dreams we’ve dreamed

And all the songs we’ve sung

And all the hopes we’ve held

And all the flags we’ve hung,

The millions who have nothing for our pay

Except the dream that’s almost dead today.

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath

America will be!

We, the people, must redeem

The land, the mines, the plants, the rivers.

The mountains and the endless plain

All, all the stretch of these great green states

And make America again!

The above is an excerpt from Let America Be America Again: Conversations with Langston Hughes, a collection of speeches and conversational essays by, and interviews with, Langston Hughes, edited by Christopher C. De

Santis. Oxford University Press © 2022.

“Let America be America Again,” was written amid the Great Worldwide Depression (1929-1939), by the great poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, Harlem Renaissance innovator of jazz poetry, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri, James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901–May 22, 1967). The title, I remember, was used as a 2004 presidential campaign slogan by Democratic United States Senator John Kerry, which, in 2016, took a terrifying twist, with “Make America Great Again.”

Almost a century later, in this post-pandemic possibility of a recession, Hughes’s haunting poem, in an awkward way, captures my ambivalence towards Juneteenth National Independence Day, a law signed, by President Biden in June 2021, which commemorates the end of “American slavery.” It is now one of 12 federal holidays.

What should provide pause during widespread Juneteenth celebrations, is not the seemingly rushed “racial reckoning” efforts following 26 million people protesting police violence, notably the live-streamed 2020 murder of George Floyd, nor non-Black folks mingling and mixing in the traditional culturally specific festivities. What is troubling as diversity, equity, and inclusion endeavors in corporate and education spaces are contested, battle cries against critical racism theory are broadcast in every medium, and laws banning books are emboldened is the lack of difficult debate of what “freedom” means, for who, to what degree, and how might it be sustained, given Supreme court rulings eroding Black people’s hard-fought human, civil and voting rights. And so, misinformation and myths about Juneteenth persist.

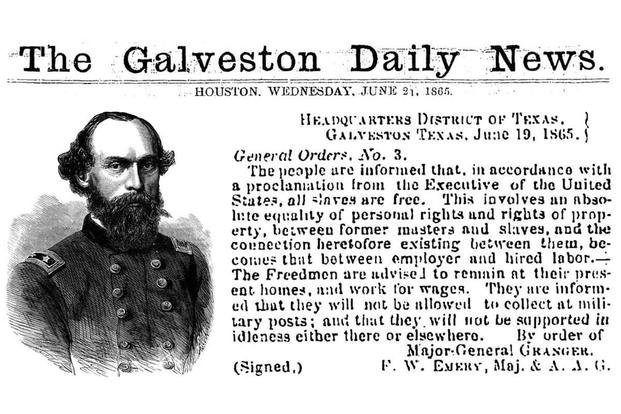

What’s in the name of June’teenth? It is a combination of the words June and nineteenth. Two days before the summer solstice on June 19, 1865, two months after the Confederates States surrendered ending the Civil War, and more than two years after President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, signed an executive order, The Emancipation Proclamation, which ostensibly freed, “all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State…” was when Black people in Galveston, Texas got the memo General Order No. 3, by US Army General Gordon Grainer,

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the

Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that

between employer and hired labor. The ‘freedmen’ are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and

that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.” Source link: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/18277837.

Before Union Troops posted the Order on bulletin boards around town, and Texas newspapers printed it, leaks were reported. According to the Official Record of the 29th Regiment USCT (United States Colored Troops), Third Brigade, Second Division was in Galveston on 18, 19, and 20 June; it reads, “June 18 …the news of freedom came by boat to Galveston, Texas… According to folklore, Black stevedores who were loading and unloading ships at Pier 21 got wind of the news and leaked it before the official announcement was made.” According to a former captive, Felix Haywood, “Soldiers all of a sudden was everywhere. Coming in bunches, crossing, walking, and riding. Everyone was singing. We was all walking on golden clouds: hallelujah!” And, National Archives’ Pension Records, published in Black Civil War Soldiers of Illinois, show Captain William E. Daggett, commander of Company F, who served over 18 months with the 29th USCT in Galveston, represented Illinois on the first Emancipation Day

Pricky plantation owners, resenting it, reluctantly communicated the ‘negative’ news to their former captives. The Bill of Rights Institute raised two Comprehension and Analysis Questions:

1. How does General Order No. 3 fully

execute the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863? What does the more than 2-year

gap reveal about the complexity of ending slavery?

2. What does this order suggest

freedmen should do in their new position? Why might this suggestion lead to

future problems between freedmen and landowners?

This Order got sporadic compliance due to the departure of the Union Army’s massive military presence. Even so, it motivated thousands of brave Black Texans to form ‘Freedom Settlements” from 1865 1930. This was a seemingly impossible task, given the State’s Black Codes legislation and the 1866 Homestead Act that banned them from accessing the 160 acres of public land available to each White settler

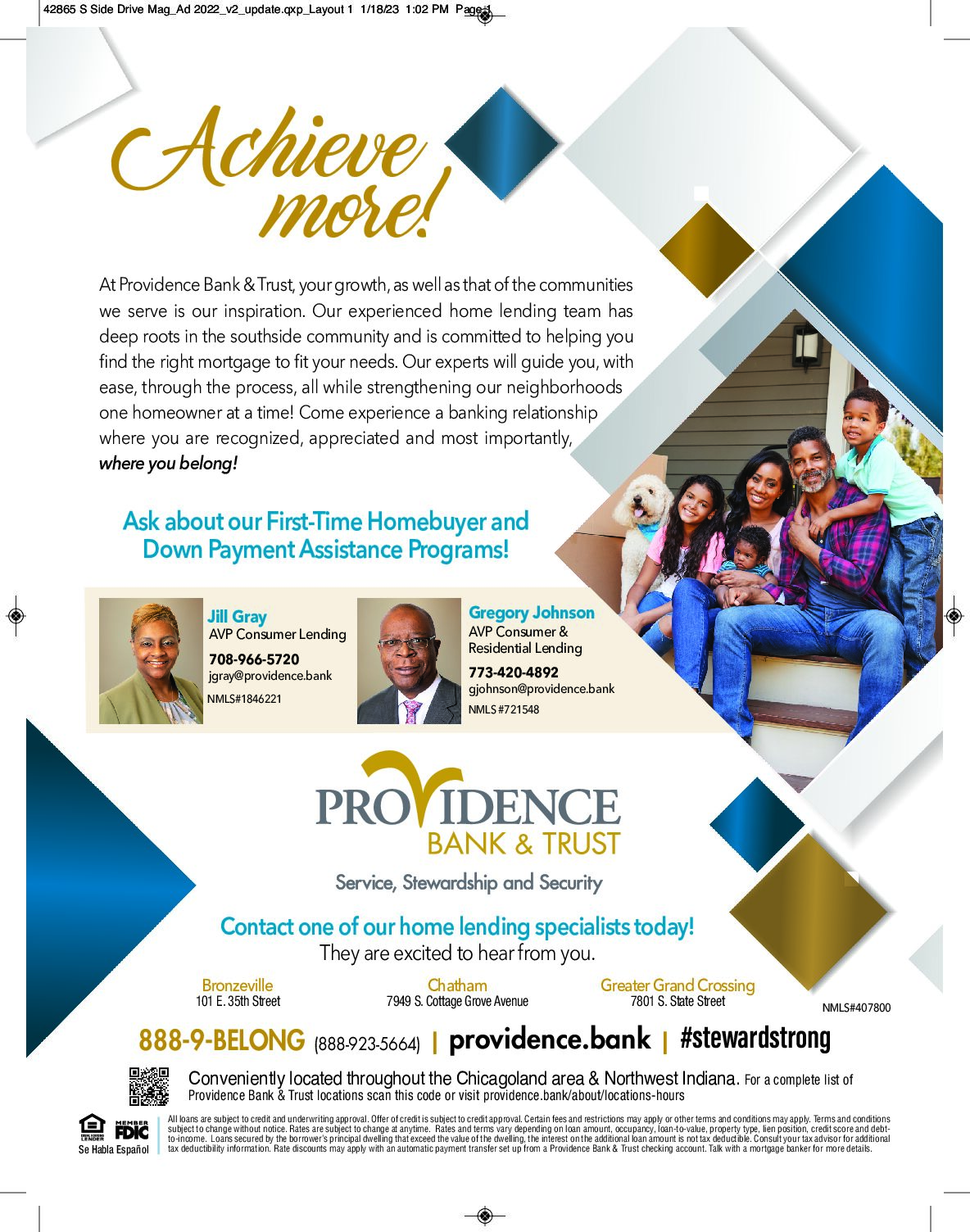

Andrea Roberts, Texas Freedom Colonies Project (TFCP), map

Their assertion of self-determination was verified by Dr. Andrea Roberts, an Associate Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning and Co-Director of the School’s Center for Cultural Landscapes at the University of Virginia’s (UVA) School of Architecture. To draw attention to the resiliency of Texas Black communities, through archival research and community outreach, she founded the Texas Freedom Colonies Project (TFCP) in 2014.

As a multimodal research and social justice initiative, affiliated with Texas A&M University, Roberts documents how these people accumulated land via cash purchase or adverse possession, and founded 557 historic Black settlements or towns, on the edges of plantations and city boundaries and often in coastal or flood-prone bottomlands.

Emancipation Day June 19, 1900, Austin, Tx. Juneteenth Celebration, (Grace Murray Austin History Center)

All over the South, freed Black people seized the opportunity of Union General William T. Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15, issued on January 16, 1865, which set up 400,000 acres of liberated land from South Carolina to Northern Florida. Over 40,000 people established self-governing ‘freedom enclaves’ with schools, businesses, civic organizations, and churches. Tragically, however, their dreams dried up like raisins in the sun, after President Abraham Lincoln, was assassinated 14 April 1865.

While Congress was not in session, the newly sworn-in, ‘people as property’ owning President, Andrew Johnson, pursued programs to reconstruct the Confederacy, advance States’ rights, pardon the traitors (provided they took an Oath of allegiance to the Republic), and later enacted an executive order repealing Special Field Order No. 15. His command coalesced sociopaths into a swarm, who like locusts, later disappeared many Black communities of resistance, leaving their descendants to tell the story.

Elsewhere, in this post-emancipation era (1865-1877) a time of terror and uncertainty ‘free-ish’ Black folks were coerced to relinquish property back to the former White landowners and then forced into forms of farm tenancy as day laborers, sharecroppers, or into convict leasing schemes used by local governments and States to exploit a callous clause in the 13th Amendment allowing mass incarceration of persons convicted of crimes. Writer, Douglas A. Blackmon explores this in, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II.

This system of oppression kick-started what Syracuse University political science professor, Elizabeth F. Cohen terms dilemmas of citizenship and semi citizenship. In other words, “whose” rights count, and to what extent? Unlike European immigrants who obtain full citizenship, the Reconstruction Amendments (or Second Constitution) awarded Black people, semi-citizenship status with partial bundles of political rights. Laws, legislated and/or those created by court order, for example, affirmative action, voting, or civil rights, make semi-citizens’ status precarious laws may be meagerly enforced or overruled. Pursuits of happiness may be ostracized or criminalized.

Since the 17 June 2021 Presidential Proclamation, many stories of Juneteenth recklessly conflate it as equivalent to the settler colonists’ Declaration of Independence from England, on July 4, 1776. That’s absurd. The tricky truth is, General Granger’s Orders No. 3 and also No.4, and including enforcement efforts of them, exclusively constitute, only those essential elements commemorated by the Juneteenth holiday.

What started on 19 June 1866, as an ambitious affair of what Black Texans called Emancipation Day, where 250,0000 folks gathered, shared meals, debated ideas, and held oratorical contests, along with dancing, singing spirituals, processions, and prayers, gradually gained significance as those freedom communities’ descendants, relocated to various parts of the country. Many held ceremonies in cemeteries to honor their ancestors, especially Civil War Colored Troops. Later, their ancestral tribute evolved into the nation’s Decoration Day, 30 March 1868, (renamed Memorial Day in 1971).

Emancipation Day is celebrated in 1905 in Richmond, Va., the onetime capital of the Confederacy.

Currently, Emancipation Day has become an annual ritual of national remembrance, commemorated in homes, schools, churches, and community centers, with barbecues, parades, picnics, poetry slams, concerts, and cultural galas. Also, several unofficial Juneteenth flags have been created (though not widely known and embraced).

What’s not widely known is what those remarkable Texas liberty leaders inaugurated, embodied, and enacted within their freedom spaces: seven principles unity, self-determination, collective work and responsibility, circular economics, purpose, creativity, and faith; they cultivated wealth in relationships. Sounds familiar? They actualized what’s now the post-Christmas celebration, Kwanzaa, one hundred years before activist and author, Dr. Maulana Karenga imagined it in 1966.

In an interview, Dr. Karlos K. Hill, author, community-engaged scholar, and Professor of African and African American Studies at the University of Oklahoma, says, “ I think that Juneteenth is a necessary moment of observation because our government and, to a certain degree, our nation and our culture has not really acknowledged the trauma of 4 million enslaved people and their descendants. It hasn’t acknowledged the impact this institution has had on this country and continues to have on this country. There hasn’t been a national accounting, and I think the Juneteenth holiday is kind of a reminder of that. And it will continue to be a reminder and a haunting until we do. It’s necessary, but it isn’t sufficient in terms of what we need to when it comes to acknowledging this history.” So, in your Juneteenth family and community gatherings, remember all our ancestors’ trauma, tenacity, and triumphs, and heed blues singer, Howling Wolf’s warning, “Evil is always trying to ruin your happy home.” Evil never rests, and neither should we. In essence, everyone is still ‘free-ish.’ Every generation, everywhere, must free the future to bring fairness and goodness into the world.

Learn more:

[The Texas Freedom Colonies Project: Thick-Mapping Vanishing Black Places: https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-texas-freedom-colonies-project-thick-mapping-vanishing-black-places.htm]

READ, HOT AND DIGITIZED: THE TEXAS FREEDOM COLONIES PROJECT

https://texlibris.lib.utexas.edu/2022/01/read-hot-and-digitized-the-texas-freedom-colonies-project/

P.R. Lockhart. Jun 19, 2018. Why celebrating Juneteenth is more important now than ever: (interview with Karlos Hill; watch video). https://www.vox.com/identities/2018/6/19/17476482/juneteenth-holiday emancipation-african-american-celebration-history