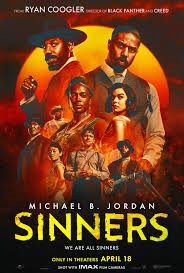

Ryan Coogler’s auteur breakout “Sinners” is a cinematic tour de force. The filmmaking wunderkind has vastly exceeded expectations with the first film he’s conceived, written, and directed being widely hailed as a classic. Coogler was already seen as a master craftsman for his work as director of “Fruitvale Station,” a well-regarded film about police-community tensions, and his classy expansion of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) with the very popular and very profitable “Black Panther” and “Wakanda Forever” films. Proof that he is well-regarded by the major studies was his selection to direct “Creed”, a film in the prestigious and profitable “Rocky” lineage.

“Sinners” is a visual feast, with stunning panoramas, expansive tracking shots, and deeply hued color tones. Initially pushed as a black horror tale, sort of in the “Get Out” mode, it is so much more. First of all, it’s a period piece, full of poignant historical insights that contextualize the lives of the major characters in that era.

The horror element is introduced through the existence of vampires, whose greater horror is as metaphors for the expropriation of Black culture. And even while performing that thematic double-entendre, Coogler managed to showcase how entangled the histories of African, Native and Irish Americans were in that part of the South. Attentive viewers would also have learned of the ethnic rivalries that were rocking Chicago during the Capone era, through the occasional screenshots of Chicago newspapers.

The film’s soundtrack is virtually another character, setting the colloquial mood while making the case that the Blues is the aesthetic fount of American music, with both sensual and sacred impulses. Coogler also throws in some hints about the metaphysical powers of twin siblings. All of this is a lot of symbolic weight for a commercial film (i.e., one expected to make a profit) to carry, but he does it with the confidence and panache of a wizened culture conjurer. Yet, Coogler is not yet 40 years old.

What distinguishes great art is its capacity to keep observers interested while they’re being shot full of artistic insight. That’s a difficult chore because insight is boring to most folks. “Outsight” (i.e., titillation of the senses) is what usually gets our attention; thus, our entertainment tends to overlook insight. “Sinners” manages to jam significant insight into some very outsightful scenarios.

Perhaps I’m being too arch here. If so, it’s because I don’t want to reveal too many specifics about a film best seen without preconceived notions. Admittedly, that’s hard to do with all of the hoopla concerning “Sinners” — but spoiler-free reviews are always the most respectful for prospective viewers. There is, however, one particular scene I don’t mind revealing. It takes place in the juke joint, which is the film’s pivotal location. It’s a short scene, but it’s one of the most moving film passages I’ve yet experienced at the movies. It’s a surrealistic, time-spanning montage of African-born musical genres conjured by the voice of the powerful Blues prodigy, played and sung by Miles Caton. The haunting soundtrack and (if viewed at an IMAX theater) the film’s shifting aspect ratio combine to amplify the scene’s mystical effect. Bro. Caton, from Brooklyn, is a newcomer to the acting craft, but his voice is vintage, and that scene is magical.

Caton may be a newbie, but the film is loaded with vets, including Michael B. Jordan (who plays twins), Delroy Lindo, Hailee Steinfeld, Omar Miller, Wunmi Mosaku, and Jack O’Connell. Jordan effectively plays two roles as twin characters, Smoke and Stack. Coogler’s inclusion of twins (and the need for Jordan to portray characters with such nuanced distinctions) as dual protagonists presents complications that are unnecessary unless there is a greater point to their presence. There is a point and, like much in this layered production, it’s an allegorical one.

The entire film moves at that poetic pace; allegory and metaphor are everywhere. When Lindo, as the character Delta Slim, tells a horrific tale of a racist lynching as the quartet (Lindo, Caton, and “the twins”) motors through vast, scenic cotton fields, Caton’s musical response perfectly illustrates Blues’ role as therapy for a victimized people. Check the skies for huge vultures landing at portentous locations. Even when Smoke takes the time to give a negotiating lesson to a young girl he asked to watch his car, it has the gravity of significance. Coogler seems too young to summon such significance from what ostensibly is a vampire movie set in the segregated South. But his prior movies — Fruitvale Station, Creed, The Black Panther, Wakanda Forever — have all been well-reviewed and financially successful, so obviously, his youth has been no barrier to filmmaking expertise. But this film was not a fictional franchise or the dramatization of a real event, as were his other films. This one was off the dome, as they say.

Every one of his films featured Jordan in a leading role. Jordan is to Coogler what Robert De Niro is to Martin Scorsese (or Denzel Washington to Spike Lee), thus the above reference, and thus the two’s extraordinary connection. The Smoke/Stack twin conceit is inconceivable without the simpatico sensibilities of Jordan and Coogler, and perhaps the director wanted to exploit the uniqueness of that bond for this film. Still, adding the complication of twin protagonists, with the same actor playing both parts, seemed to be biting off much more than necessary. But Coogler thoroughly chewed what he bit off.

While initially presented as a vampire movie, in the tradition of Robert Rodriguez’s stylish “From Dusk till Dawn”, Coogler’s epic uses the vampire trope as somewhat of an intervention into the South’s deadly racial drama. As I noted earlier, it juggles weighty issues with such casual aplomb that they fade into the scenery. Its historicity teaches as it engages. There is one tracking shot, for example, that follows the daughter of a Chinese store owner (another historical nugget: there was a significant Chinese population in Mississippi during the first decades of the 20th century) from one side of the street to the other, and we see the strict racial segregation that characterized the era as she moves. No need for exposition, the cinematography made the point. This audacious film contains similar gems in virtually every frame; it’s almost a miracle that it is also so entertaining. But it is. And being that it manages to be both entertaining and enlightening, “Sinners” is one of those rare aesthetic milestones that help us chart our future by illuminating our past.

Speaking of the future, much is being made of Coogler’s deal in which he will attain complete ownership of the “Sinners” project in 25 years, called an ownership inversion. That seems entirely appropriate to me in how it adjusts financial calibrations between artists and the industry. Only a select few proven filmmakers can demand this kind of arrangement (Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Martin Scorsese), but these adjustments will become even more germane as modern technologies progressively encroach on artistic prerogatives.

Salim Muwakkil is the host of The Salim Muwakkil Show on WVON-1690 AM Saturday’s from 7 pm – 10 pm, and Senior Editor of In These Times Magazine.