The Reverend Dr. Brian E. Smith, DMin

Director of Community Relations and Strategic Partnerships

Chicago Theological Seminary.

I have had the privilege to journey with hundreds of pastors and community faith leaders across the United States. During the past five years, I have worked closely with the Rev. Jesse Jackson Sr., his family, and members of the inner circle who were with him at the origins of his career. Not only have I witnessed his genius and magnificence, but I also have come to appreciate the brilliance of those who have collaborated with him.

No great movement occurs without a cadre of competent, faithful individuals who share the leader’s passion and commitment. Rev. Jackson’s entire team has been as magnificent as he has been. The team is familial and community oriented. Team members are also diverse in terms of their racial, gender, and religious identities.

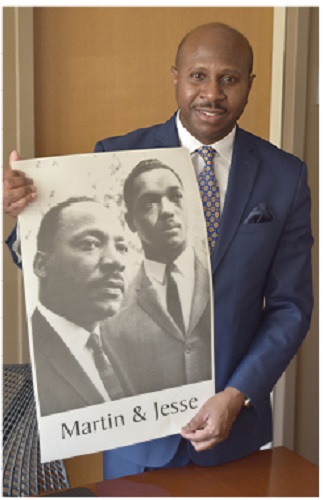

While Rev. Jackson’s ministry is multifaceted, there is an obvious dualism in his illustrious and fruitful career in civil rights and social activism. On the one hand, in the biblical sense, he can be viewed as a Joshua, a protégé to the venerable prophetic figure, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On the other hand, in the political sense, Rev. Jackson is the precursor to President Barack Obama. Jackson and the inimitable Congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, who preceded Jackson, were both courageous forerunners in the relay for the United States to have its first black president.

The scope of Rev. Jackson’s influence and impact is broad and deep, as he has remained fiercely committed to the call and mission of building the beloved community. Dr. King, Jackson’s mentor, believed that the beloved community involved full justice, especially for historically marginalized communities. Full justice entailed not only the right to equality and dignity but also the right to material equity and even prosperity. King understood that the disinherited cannot be absolutely free when they are hungry, homeless, and impoverished.

In the later phases of his ministry, Dr. King pivoted to a more acute focus on the economic dimensions of social justice. Accordingly, he set his sights on northern cities in the United States to address systemic poverty. The City of Chicago proved to be fertile ground for sowing seeds in this new endeavor.

Dr. King selected three seminary students from Chicago Theological Seminary (CTS). CTS had a longstanding reputation for supporting progressive social change. Nearly a decade earlier in 1957, CTS became the first seminary in the United States to award King an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree for his activism in the civil rights movement. Thus, the relationship between King and CTS was the predicate for why King believed that CTS would be a reliable resource for finding courageous, emerging leaders. 2

Two of the students whom King selected were young white men—Gary Massoni and David Wallace—and one was a young black man—Jesse Jackson, Sr. In this selection, we witness King’s deliberate calculation to build the beloved community across racial boundaries. Jesse and his revolutionary compatriots Gary and David willingly accepted the assignment to fight specifically and deliberately for economic justice.

To fully comprehend Rev. Jackson’s impact on national and international politics, one must understand how deeply enmeshed he has always been in religion. He is a trained ministry professional. Jackson and his partners—Massoni and Wallace—formed a cohort of interracial brothers who were spirit-filled, and the esteemed faculty at CTS rigorously equipped them with global perspectives on ministry and service.

These three young students grappled at CTS with the intellectually demanding writings of the theological titans of the time, such as Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich. These young revolutionaries were eager to make abstract theological ideas come alive in the flesh—and especially on behalf of the wounded flesh of black people who were being lynched by angry mobs, bitten by vicious attack dogs, and lacerated by the skin-piercing flow of fires hoses that enflamed racial bigotry instead of extinguishing it.

Consequently, Rev. Jackson and his colleagues had to submit themselves to uncomfortable and threatening circumstances. Neither the pristine halls of the academy nor the stained-glass sanctuary of cathedrals could serve as the primary context for their revolutionary action. Instead, the pavement of city streets became their pulpit. And like Jesus, they ministered to the masses whom they met on the streets, and they encouraged the masses to join the revolution.

Their actions teach us that public ministry grows from the ground and does not descend from the clouds. Furthermore, public ministry, like shepherding, is often messy. Shepherds of the public square do not have the luxury of serving in pristine environments. They must lead and establish justice in messy spaces.

Rev. Jackson understood this, and when it came time to facilitate a movement for more economic justice, he left the sanitized realm of the academy and encouraged his classmates to venture into the messy world of Selma—the same messy world that existed in Chicago and many other northern locations.

However, the messiness of racial injustice had remained hidden to many people in the United States until Dr. King’s presence in Chicago communities like Cicero revealed that racial bigotry was arguably even more intense and acute in the north than it was even in the south.

When Jackson and his friends visited Selma, the theological concepts of the classroom, to quote from the Gospel of John, “became flesh and dwelt among us.” When injustice is embodied in tangible, death-dealing ways, intangible theories alone will not suffice. Jesse and his band of social justice siblings were quintessential community organizers. Like Jesus, these revolutionaries served the community by organizing the community. 3

They were never afraid to be among the least, the lost, and the left behind. In short, shepherds of the public square are comfortable with the folk, know how to talk with the folk, learn from the folk, and keep it real with the folk. This template for vigorous community organizing provided the framework and laid the foundation for the emergence of Barack Obama as a serious presidential possibility. The Obama campaign leaned upon the networks and expertise of many black, Chicago based soldiers of the movement. Rev. Jackson’s was a primary trailblazer and prototype who demonstrated the possibility that President Obama would actualize throughout his historic presidency.

Undergirding Rev. Jackson’s venerable political activism is a profound measure of faith. Indeed, Rev. Jackson at his core is both an activist and a priest. In his priestly role, he has consistently embodied the tenets that Jesus claimed in his initial sermon while reading from the prophet Isaiah, “The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good news to the poor; the Lord has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound.”

Rev. Jackson has served as a priest to countless people who are brokenhearted and bound by the shackles of economic vulnerability. For example, during the Christmas season, Reverend visits the incarcerated and food is dispersed to the community as well as goods for young mothers and their children. The headquarters of Operation Push remains a storehouse for those in need.

Furthermore, so many disenfranchised people heard the “good news” of democratic participation proclaimed by this priestly preacher. Consequently, the number of people who registered to vote, and who actually have voted in elections, increased in substantial ways through Rev. Jackson’s insistence on the sanctity not only of the Bible, but also of the ballot box. In stark contrast to past and present anti-democratic plots that have prevented people from voting, Rev. Jackson’s ministry has empowered people to vote.

Rev. Jackson also takes time to visit the sick and pray with those who are troubled and in need of a spiritual presence. When the media’s microphones and cameras are not on, I have witnessed Rev. Jackson praying in private, engendering precious moments with community leaders whose families are dealing with grief and pain.

Rev. Jackson has always understood the power of prayer. As a prophet and a priest, he understands there is a time and season to fight for God’s people and to pray for God’s people. As Rev. Jackson has consistently declared across the years to “keep hope alive,” he is telling us to hold fast to the dynamics and form of justice even when it appears to be dead. Rev. Jackson’s mantra and leadership are a clarion call to actualize justice and make it tangible among us. Both Dr. King and Rev. Jackson understood that social justice, apart from tangible and experiential realty, is superstition. Theoretical or abstract justice is an insult and mockery to those who experience injustice. Abstract justice is also a harmful placebo that further disempowers the disinherited.

When Rev. Jackson calls on the masses to keep hope alive, he is urging us to fight faithfully against the nihilism and grief that often accompany injustice. The refrain from the Negro spiritual, “Keep Your Lamps” tells the listeners to be in a state of readiness, keeping the lamps trimmed and burning while encouraging them to continue the journey saying, “Children don’t get weary.” The slogan from Rev. Jackson’s campaign was “Run Jesse Run.” Like a powerful 4

sprinter on a relay team, Jesse ran and handed the figurative baton of opportunity to Barack who ran successfully for the presidency.

Moreover, Jesse’s running has motivated many other courageous, competent leaders to run for the highest offices in the United States. This illustrious list includes, but is not limited to, Vice President Kamala Harris and United States Senator Rafael Warnock. We know that the race is not given to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, but rather the winners are those who endure. Rev. Jackson’s running between the time of King and the time of Obama reminds us of the importance of each of us running the race that is assigned to us. Because of this legacy, we all need to run a little while longer.

Thank you, Rev. Jackson, for teaching us to actualize our freedom while recognizing that liberation is an action not a concept. Thank you for leading with non-violence and showing that love is the most powerful instrument for peace and good-will on earth.

Thank you for being kind and taking the time to encourage people from all strata of society. as we understand the kind of person you are by how kind you are. Thank you, Jesse, for being faithful and for fearlessly running your race with courage. Because of you, we absolutely will… “keep hope alive.