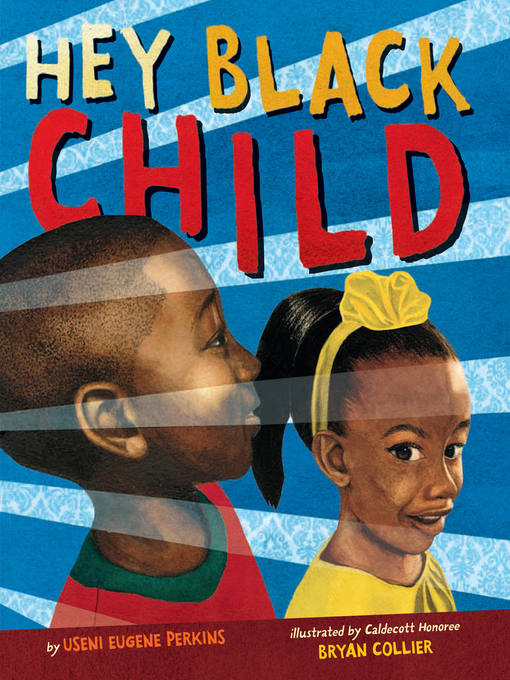

Useni Eugene Perkins, the Chicago-based poet/activist/playwright, best known for his 1974 poem Hey Black Child, died Sunday morning (May 7). Poet, playwright, essayist, historian, social service pioneer, and author, Perkins died peacefully after a brief illness and hospital stay.d.

His use of rhythm and repetition, combined with an empowering message for Black children, made “Hey Black Child” a classic taught even today

in preschools and classroom across the U.S. The poem, originally a song lyric

used in Perkins’ 1974 play The Black Fairy, appeared on a popular poster made by Perkins’ brother Toussaint bearing the word “Useni” (“tell me” in Swahili), with no other reference to authorship. As such, the poem is often mistakenly attributed to Maya Angelou or Countee Cullen or confused with other works titled “I Am the Black Child”.

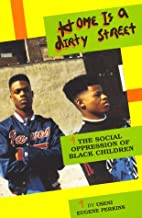

Julia Perkins says her father was “a renaissance man who believed in Black people”. She added his “hundreds” of poems, and other works like the 1975 non-fiction 1st-hand account of working with Chicago’s Black youth Home Is a Dirty Street, “uplifted our people, and prepared the path for African Americans” during the artistic and social movements he helped pioneer in the 1970’s.

Perkins, son of famed sculptor Marion

Perkins, combined art with social activism and community service, setting

the model for 21st century artist/activists like Nipsey Hustle, Vic Mensa, and Che “Rhymefest” Smith, among others. During the time he rose to prominence Chicago wasn’t NYC or LA, so even “famous” artists needed day jobs to survive. It’s much easier to be “well-known than it is to be “well-off” was a popular saying back then.

Like many of his peers in the Chicago Black arts & culture community, Perkins had a professional career based in community service, serving as director for the Better Boys Foundation (BBF) Family Center for nearly two decades (1966-82). In addition to his time at the BBF, in the 1980’s he briefly served as interim director of the Chicago Urban League, and as interim president of the DuSable Museum of African American History. During the 1970-80’s as a leader and pioneer working with Chicago’s at-risk youth, Perkins served on task forces convened by the Chicago Board of Education and the State of Illinois, helping to develop youth violence prevention and youth development.

“He showed us how to move from thought into action” former DuSable Museum president and CEO Carol Adams said, as she described the energy behind many of the projects they worked on together. “He would commit strongly to whatever he did for the community and gave himself thoroughly”. Adams recalled a visit Perkins made to the Youth Correctional Center in St. Charles Illinois that sparked an organized effort to visit and engage with young people serving time in Illinois prisons. “Eugene said there were young men in there that no one came to visit,” Adams said, prompting her and other colleagues to organize visits to Statesville, Vandalia, and other prisons.

The same year as “Hey Black Child” was published Perkins and Adams were among the founders of CATALYST (my mother Myrtle Taylor also a member), an organization of Black Chicagoans educated and employed as social workers. The group also included the dramatist and future theater director Abena Joan Brown, the future broadcaster Warner Saunders, and Civil Rights movement icon Al Raby.

Perkins was also one of the Black writers, artists, and intellectuals like Haki R. Madhubuti (nee Don Lee) at the vanguard of 1970’s-era Black Arts Movement, people who viewed their art and work as part of the Civil Rights and Black liberation movements of the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. He was a central figure in the Organization of Black American Culture, (OBAC) bringing together Black artists, educators, activists, and thinkers like Negro Digest editor Hoyt A. Fuller, the poet Conrad Kent Rivers, and historian Abdul Alkalimat (nee Gerald McWhorter).

His catalog of literary work spanned over five decades, including poetry collections, social commentary, and a 2017 children’s book with reprint of “Hey Black Child, most published by Madhubuti’s South Side-based Third World Press. Just recently Perkins wrote the forward to a collection of poems self-published by Carol Adams.

His combination of arts, activism, and community service was a living model still used today by “artivists” and other community advocates. Yvette Moyo, CEO of Real Men Charities, Inc., said Perkins was “a friend and big brother figure” whom she described as an “art activist” who “kept me focused on why I was doing what I did”. David Robinson, a self described practivist and Director of External Affairs at Manufacturing Renaissance, called Perkins “another titan in our centuries old struggle for a place of respect and equality in this country”. Robinson (the son of late activist/organizer Buzz Palmer and former Illinois State Senator Alice Palmer) added “I have been blessed to be among those who experienced his wisdom, his poetry of tussle with formidable others, and his unwavering commitment to the people through verse and deed. We must carry this work forward.”

Like many of his peers in the Chicago Black arts & culture community,

Perkins had a professional career based in community service, serving as

director for the Better Boys Foundation (BBF)

Chicago-based freelance writer/editor and “city-country bridge builder” Bonni McKeown recalls meeting Perkins in the early 2000’s when helping her partner, bluesman Larry Taylor write his

autobiography. Perkins’ 1987 book Explosion of Chicago’s Black Street Gangs made a particular impression on her. “I find much in this compact book still relevant from what seems to be going on now,” McKeown said, noting that it “mentions the incomplete understanding of the situation by liberals who look like me, and their failure to consult Black social workers familiar with the streets”.

I’ll remember Baba Perkins first as a South Shore neighbor and dear friend of my late Dad Elworth Taylor and 90-yrs. young mom Myrtle, who made learning “Hey Black Child” an unwritten requirement of attending the South Side preschool and elementary schools she ran for 30+ years. His encouragement of my youthful pursuits in poetry was a small but potent confidence booster; he later provided a living example I could follow to pursue my careers in journalism and music.

Even if I’d have known as a kid how famous Eugene Perkins was as a poet, it’s likely I wouldn’t have been star-struck around him. Baba Useni Eugene Perkins was one of the “community elders”, some ancestors and some still here*, those mentioned above and others like Henry English, Wellington Wilson, Bob Starks, Conrad Worrill, Bob Black, Oscar Brown, Jr. Phil Cohran, Jean Pace, Margaret Taylor-Burroughs, Askia Muhammad, Earl Calloway, The Dozens, Homer Franklin, Charles Kidd, Harold Pates, Leon Chestang, Bobby Wright, Patricia Hill, Ramsey Lewis, Paul Serrano, Jessie Jackson, Sr., Willie Barrow, Henry Hardy, Alice Tregay, William Cousins, Vernon Jarrett, Harold Washington, on-and-on, out there doing stuff for Blac people. Art, life, scholarship and thought, service to Black people and community, all part of daily life. You could see the results of what they did, piece by piece, change you could see happening slowly, gradually.

They were simultaneously larger-than-life and people I could see and talk to. You might see them in the media sometimes, but you’d see them more often doing stuff for Black people in the places where we lived. To Be It you have to See It- his example of this is the biggest gift Baba Eugene leaves to all of us.

Bit by bit change comes. Yes, gun violence is a cancer on our communities, but when Black people first came to South Shore and the Southeast Side there were parks, beaches, and other areas that were definite No-Go Zones for non-white people. Rainbow Beach/Park was a 15-minute bike ride from my house, but if my friends and I ever tried to go there, white kids (and some adults, too) would have probably run us out of there. There would have been many more of them than us, so we didn’t try it. I went to kindergarten at a neighborhood school, but never set foot inside Rainbow Park until I was a teenager. Would white kids have faced similar problems in our part of the Southeast Side? I Don’t think so There were more than a few white families where I lived. But Chicago circa ‘70s meant we likely didn’t have anything in our neighborhood that white kids didn’t have threefold in theirs. So no reason for them to visit.

My friends and I asked our parents “Why do they hate us so much?”. It is hard to explain to young people today how racism back then was not just about important structural issues like criminal justice or whether people hate or exclude you, but how damn hard racism tried to make you feel inferior. That’s why “Hey Black Child” was so important back then, and even more so today. Baba Useni did his part. The eternal optimist in me says we’ll eventually figure out how to fix the problems we have now.

Perkins authored numerous books, among them “Hey Black Child,” “The Rise of the Phoenix: Voices from Chicago’s Black Struggle, 1960 – 1975;” “Home is a Dirty Street: The Social Oppression of Black Children” “Black is Beautiful,” and many more.

Baba Useni is now with the ancestors.

Rest well. Ashe’