By Emma Young

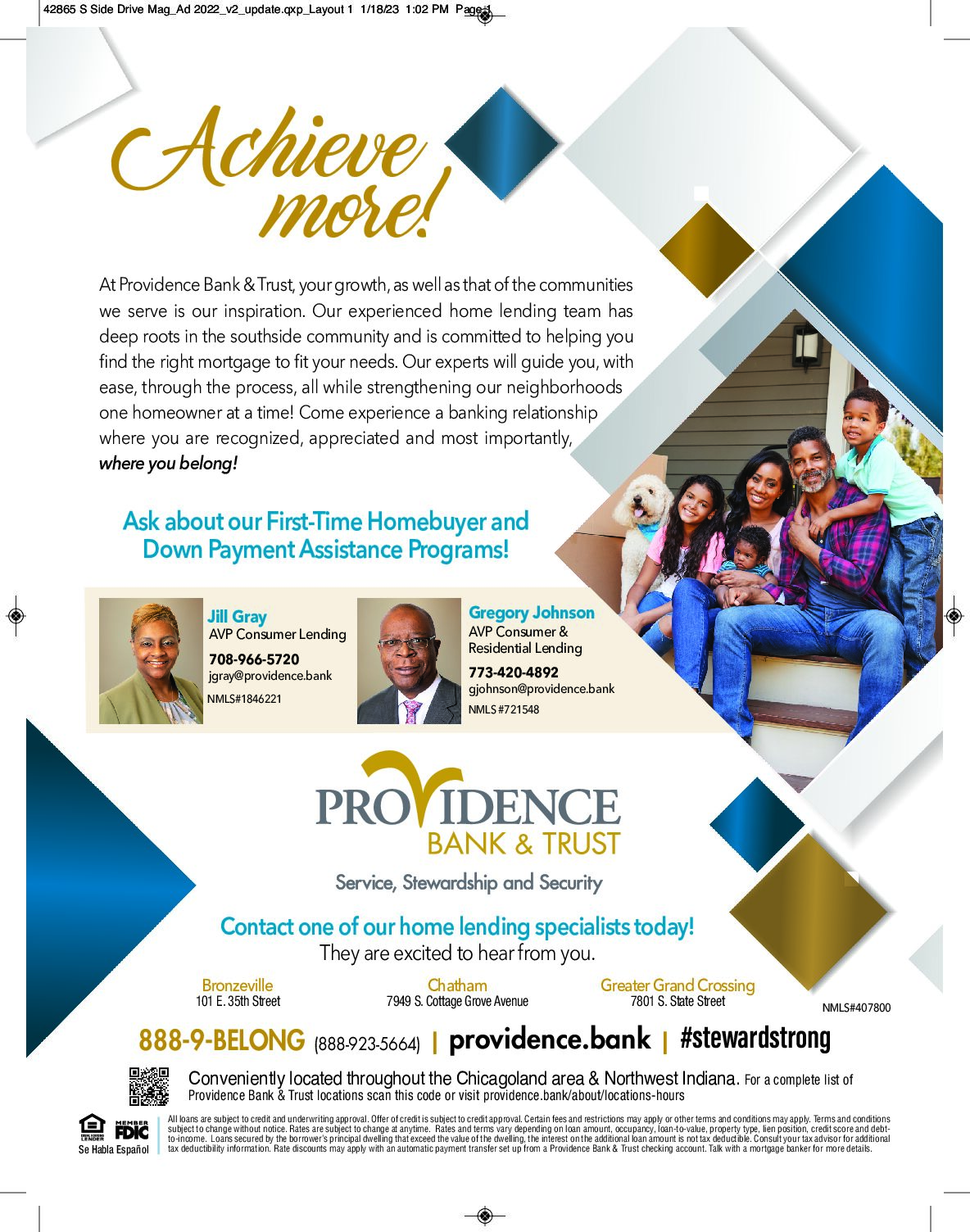

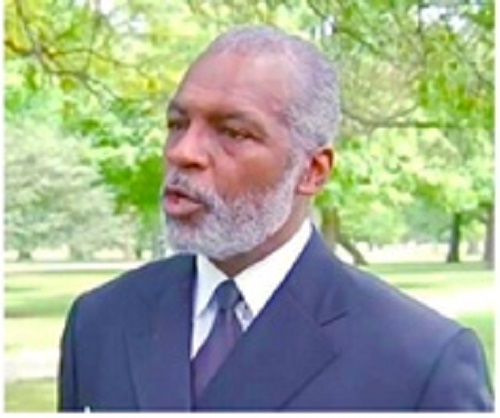

The term “investing in people” has been bandied about a lot lately. But what exactly does that mean in a city such as Chicago? Does it mean investing millions in developments of multi-tier market-rate apartment complexes? Or does it mean placing high-end stores in low-end communities? Neither, says Mark Wallace, cohost of The People’s Show and Executive Director of both the Citizens for the Abolishment of Red Light Cameras and 10 X 10 to Win in Illinois. In fact, Wallace cites what he feels is the perfect model for investing in people.

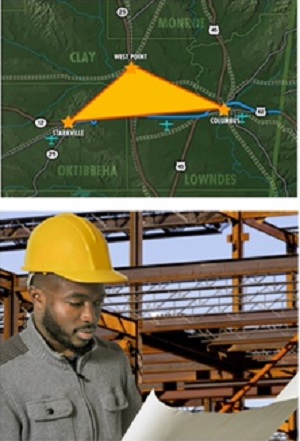

According to Wallace, this idea grew in three of the poorest counties in Mississippi. “They were suffering and hemorrhaging at twenty percent unemployment,” Wallace says, “they were losing manufacturers left and right. They had lost more than twenty-four manufacturers in that region, and their largest employer, Sara Lee, had folded up and left. They just did not know what to do.”

So, Wallace goes on to tell us that the three counties got together in that area and they did a tri-county joint venture. They hired a head-hunter by the name of Joe Max Higgins, and at the time, all they wanted from Mr. Higgins was for him to bring a movie theater to the region. Higgins told them that he could bring them a movie theater, but with the high rate of unemployment and economic depression, nobody could afford to go to the theater.

We have 600 acres of land on the south east side of Chicago that runs up and down the lake where the old U.S. Steel Company used to be, which provided thousands of jobs for people on the south side of Chicago,” says Wallace.

After Higgins had the theater built, he pulled together all of the people who had hired him, all the politicians, Republicans and Democrats, Black and white, and as Wallace tells us, “he had to get them in the mindset of a whole new way of thinking. He said he had to get them to the point where they could think big, and they could think winning.” Then he took them on a helicopter trip, showing them all the vacant land that was dormant. (Much like the vacant land in Chicago where the steel mill used to be, Wallace points out.) Higgins said, “All this is opportunity, but we have to have the will to win, and we have to attract businesses to come here, and we have to incentify those industries to come and bring their businesses here , to hire and train people from within the area.”

Joe Max Higgins then began to solicit advanced manufacturers to bring their industries to Columbus, Mississippi in exchange for tax subsidies to offset their costs. The businesses agreed to train citizens of Columbus, Mississippi, so they would be ready to step into the jobs as soon as the plants were built.

They began with an advanced manufacturer steel plant, a helicopter manufacturer and a German truck engine building company, which brought the first 6,000 jobs. As they were putting in the roads and infrastructure for those industries, they were training the people in the community colleges.

In less than 10 years, they went from twenty percent unemployment to just above the national average at the time which was about four percent, and everybody who got those jobs was earning between $60,000 and $112,000 a year.

Wallace has been in regular contact with Joe Max Higgins and his team, hoping he could convince the mayor or some other Chicago officials to at least sit down for a few minutes with Higgins and hear the plan.

“We have 600 acres of land on the south east side of Chicago that runs up and down the lake where the old U.S. Steel Company used to be, which provided thousands of jobs for people on the south side of Chicago,” says Wallace. “Even people from the west side of Chicago worked at the U.S. Steel site, and those jobs kept our communities strong.” They kept the Black businesses on the south side of Chicago strong, he reminds us. “Businesses along 87th Street, 79th Street, 75th Street, Stony Island – we had Black businesses everywhere, because we had a strong labor force that was working in Chicago. Supporting those businesses,” he says.

Wallace is enthusiastic as he speaks about the possibilities, “That’s real investment, that’s real transformational investment and partnership that will transform conditions. You can take people who are coming out of high school, who are not headed for college, that will be able to go into a career, that will be able to start a job and retire from that job.” He goes on to emphasize, “You cannot have public safety when you have chronic unemployment of Black males between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five who are unemployed at forty-seven present on the south and west sides of Chicago versus their white male counterparts who are unemployed at seven percent in the same city. You can’t suggest or even think you’re going to have public safety with that kind of chronic unemployment in these communities.” He goes on to say, “You cannot have a safe city with chronic unemployment and high rates of poverty. Wherever there are high rates of poverty, there are high rates of violence and there are high rates of crime. Wherever there is strong economy and stable employment, you have low rates of crime and low rates of violence.”

What about the thousands of young men who are deemed unemployable because of some low level felony on their record? “We can train them!” Wallace says, “They have been felonized by a system where we’ve had this war on drugs here in the last 30 years and Chicago is like ground zero. Chicago has more Black men that have low-level felonies than any other city in America.”

“This is how we invest in people,” says Wallace, “This is how we address public safety.”

Another benefit of bringing in industries to the city is now you’re expanding the tax base. “With these industrial manufacturers paying taxes, you now take the budget off of the backs of Chicagoans, especially poor Chicagoans who pay billions in red light camera and speed camera fines, who pay millions in plastic bag costs every time they purchase groceries,” he says.

The program in Mississippi is called the Golden Triangle, because it consists of three regions. “It’s not a pilot program,” Wallace says, “It’s an economic initiative that has gotten real results over fifteen years and that is successful and thriving.”